A military base in Cambodia can act as a tool of influence for Beijing.

Updated On – 12:49 AM, Wed – 11 January 23

By Benjamin Blandin

Hyderabad: The 2019 agreement between China and Cambodia on the Ream base has recently generated a wave of concerned publications and comments. This agreement provides for the opening of facilities and the stationing of Chinese army units at the Cambodian military naval base. For many observers, Beijing is thus further strengthening its grip on Southeast Asia, along the now famous ‘string of pearls’ (an expression designating the Chinese strongpoints along the main route of energy supply from the Middle East).

What explains such a resurgence of interest, almost three years after the first revelations of the Wall Street Journal and the successive publications of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (CSIS-AMTI), even though there has not been any materialisation (in the military domain in any case) of the agreement on the ground yet?

The continued increase in tensions in the South China Sea, the lack of significant progress on the code of conduct for the South China Sea on which China and the other coastal countries have been working for nearly three decades (Declaration of Manila, 1992), and Beijing’s aggressive diplomacy in times of Covid arguably helped draw attention to any new Chinese initiative in the region. What is it in practice?

Storm in Glass of Water?

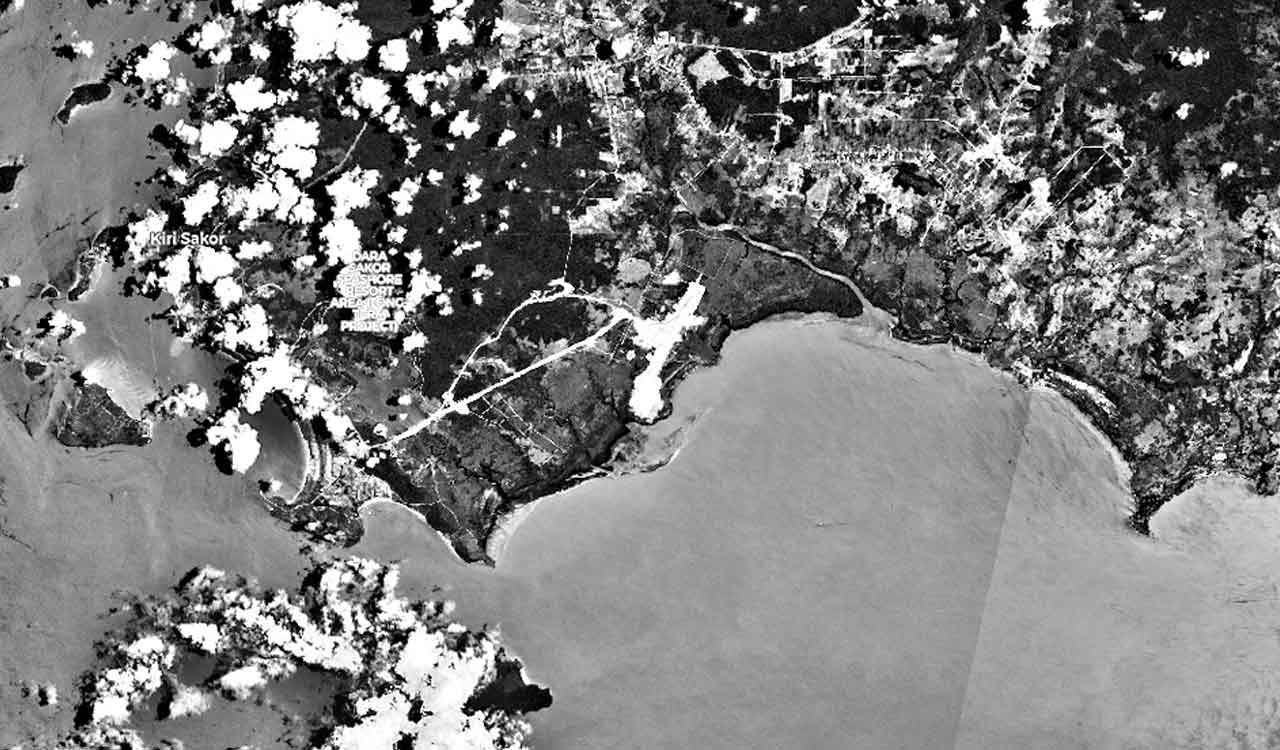

The modesty of the facilities at the Ream base, limited to a single wharf and a set of logistics and administrative buildings scattered over a perimeter of nearly 77 hectares, could suggest that there may have been a little media frenzy after the mention of a Chinese ‘secret base’ in Cambodia.

An impression reinforced by the presence of seabed of the order of seven meters deep, which only allows the docking of ships of modest dimensions (1,000 tonnes maximum), such as patrol boats. Of little strategic interest a priori for the Chinese navy, none of the main units of which could benefit from the installations as they are. And for what purpose, even though it already has formidable naval air bases in the Spratlys and the Paracels?

However, several elements raise questions, in particular the secret nature and the clauses of the agreement, which could reflect the influence that Beijing exercises over the Cambodian security apparatus and the stranglehold of Chinese networks on the country’s economy, particularly in Phnom Penh and on the coast, especially in the Sihanoukville area.

A Deal to Hide Another

Officially, the agreement aims to modernise the port facilities of the base with the technical and financial support of China to allow the reception on site of larger ships and to facilitate the Cambodian Navy in the conduct of its security missions. shipping in the Gulf of Thailand.

However, the agreement is not limited to infrastructure investment considerations, and it should be remembered that the start of construction was preceded by the destruction and removal of buildings financed by the United States and Vietnam – a precedent that has helped strain relations between Phnom Penh and Washington.

Similarly, the clauses of the agreement have never been made public, but we now know that they include, in addition to a lease on half of the base granted to China for an initial period of 30 years, renewable by tacit renewal, the ability to build facilities, dock ships and store weapons and ammunition.

Surprisingly, it would have been found that Chinese military personnel circulate armed and dressed in Cambodian uniforms or in civilian clothes, on the perimeter of the base. Chinese soldiers would also have Cambodian passports.

Exclusive Links

Moreover, it is no secret that extremely strong security ties have united China and Cambodia since the Khmer Rouge period. At the time, China indeed provided the Khmer Rouge regime with massive support to counter the invasion by Vietnam, in the midst of an ideological confrontation between China and the USSR.

Since then, China has become Cambodia’s leading arms supplier and the pace has only accelerated in recent years, with a mix of donations and sales at cost price, around $240 million for the last ten years. An amount that includes logistics vehicles and armoured vehicles, artillery, helicopters, anti-aircraft systems, uniforms, small arms and ammunition.

The situation is even more critical with regard to the Royal Navy, all of whose 15 patrol boats in service were donated in 2005 and 2007 by China – a partner from which Phnom Penh will therefore have to obtain all the spare parts, which could seriously challenge the sovereignty of Cambodia.

In the field of officer training, China has strongly contributed to the creation of a military academy whose programme was designed by the Chinese Ministry of Defense and where teaching is delivered to cadets by mainly Chinese personnel. The training also includes a mandatory six-month internship in China.

This all-out security support is also accompanied by political support for Prime Minister Hun Sen (in place since 1998), which has prompted the latter to systematically support Beijing’s interests, particularly as President of Asean , in 2012 and 2022, or by handing over Uyghurs to authorities in Beijing .

The agreement with Cambodia represents for China its second foreign establishment after Djibouti , except for the installations in the South China Sea . Once equipped, the Ream base will be able to accommodate ships weighing up to 5,000 tonnes, including most corvettes and frigates, and even some Chinese navy destroyers.

For Indonesia, whose Natuna archipelago is located equidistant from Ream and the Chinese installations at Fiery Cross Reef (Spratly archipelago), it goes without saying that the possibility offered to the Chinese navy of resupplying on both sides another part of the archipelago can only lead to an increase in pressure on its security system and its resources. This is all the more true since many clashes have already taken place in its exclusive economic zone, which has prompted it to beef up its system in recent years.

The other Asean countries bordering the South China Sea (in addition to Indonesia, this is also the case with Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia) are also worried about Ream’s installations. Especially Vietnam, a neighboring country of Cambodia, which has already experienced many border conflicts with China , not to mention the regular incidents between Vietnamese fishing vessels and Chinese coastguards .

Media stunt, backhand technique to intimidate Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia all at the same time, inexpensive reinforcement of its strategic device, show of force aimed at Asean … it must be recognised that for China, the agreement with Cambodia is as much a fait accompli as a masterstroke in what is increasingly akin to a game of Weiqi : Beijing is demonstrating all-out activism to advance its interests in the region.

Phnom Penh’s Technique

As we can see, the apparently modest agreement between China and Cambodia on the granting of permanent facilities at the Ream base is in reality of great importance from the point of view of Chinese strategy in the region.

As for Cambodia, however, one should not jump to conclusions about the kingdom’s supposed allegiance to China. In his time, King Norodom Sihanouk (on the throne from 1941 to 1955 and then from 1993 to 2004) knew better than anyone how to multiply the reversals of alliances, successively approaching France, the United States, Russia and from China. A cunning man, Prime Minister Hun Sen, who has exercised the reality of power for 37 years, has himself known how to navigate from one ally to another to stay in power.

While Cambodia’s main trading partners are the European union and the United States, the first political and security partner is clearly China. However, and this should perhaps be seen as a sign, Hun Sen’s three sons completed military studies, not in Beijing but in the United States (Hun Manet thus studied at West Point , Hun Manith at George C Marshall European Center for Security Studies and Hun Many at the National Defense University ) – proof that China does not yet control all the levers of power in the country. (theconversation.com)

#Opinion #Chinese #secret #base